History of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves

1774: A Precursor to Revolution

The American Revolution and the ensuing founding of the United States of America was by no means inevitable. When North Carolinian women affixed their names to a nonimportation agreement in October 1774, they had no way of predicting that the Revolutionary War's first shots would ring out less than six months later.

The Edenton Tea Party Resolves and the event's precursors, such as the Boston Tea Party and the First North Carolina Provincial Congress, were a symptom of the ongoing political debates of the day. These questions included: What rights did colonists have? How, were their rights different from those of other British citizens? How could colonists have their voices heard when it came to shaping governmental polices?

The Edenton Tea Party Resolves became a way for women to have a voice and to advocate politically for themselves in the same way that their male contemporaries were.1 They couldn’t know it yet, but the nonimportation movement they supported would eventually lead to the American Revolution.

The Boston Tea Party & the Intolerable Acts

By 1773, after financing the costly Seven Years War and facing a famine in parts of colonial Asia, the British government was in financial crisis. Earlier in 1767 the British government had enacted the Townshend Acts, a series of laws meant to directly tax North American colonists for goods such as glass, paper, and tea. Colonists, however, found these policies highly unpopular. It was taxation without representation, they argued, as they did not have representatives in parliament who could advocate for them. After a series of protests, Parliament eventually repealed the unpopular taxes, save for one on tea. Trying to soothe the financial crisis, in June 1773 Parliament enacted the Tea Act, giving the government-backed East India Company a monopoly on tea and other colonial trade. However, the act opened the old wounds many colonists had felt during the Townsend Duties crisis. Again they protested the unfair policy of Taxation without Representation.

Engraving depicting colonists throwing crates of tea from ships into the Boston Harbor. Later known as the Boston Tea Party, this act of protest helped lead to the American Revolution. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

During the night of December 16, 1773, a group of protesters in Massachusetts had enough. Throughout the summer they had called for boycotts on the East India Company. They rallied colonists together, calling for a repeal of the Tea Act and for the ships laden with East Indian tea to go back to England. When the colony's royal governor refused to listen to their demands, a group of the Sons of Liberty took matters into their own hands. They illegally boarded three ships and dumped 340 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor in an event that later became known as the Boston Tea Party.

In order to punish Massachusetts for the incident in the Boston Harbor and strengthen their authority in that colony, Parliament enacted a series of laws called the Coercive Acts or the Intolerable Acts. The first of these acts, called the Boston Port Act, was enacted on June 1, 1774. It closed the Boston Harbor until colonists paid for the destroyed tea, halting the whole colony’s economy due to a few individuals' actions.2

Illustration from Within Our Power: The Edenton Ladies' Tea Party depicting a flyer that reads "TAXATION without Representation." Courtesy of Jonathan D. Voss.

More concerning, the Intolerable Acts also revoked Massachusetts’ charter, placing the colony under direct royal control. Further, the act severely restricted the colonists’ right to assemble or hold large meetings.

These so-called Intolerable Acts only applied to Massachusetts, but as the news circulated, it sent shockwaves throughout the North American colonies. Many colonists feared that Parliament’s swift and harsh punishments for Massachusetts would set a dangerous precedent. For these concerned citizens, the harbor's closure and the revocation of both the charter and the right to assemble were signs of massive governmental overreach. Further, the acts only heightened preexisting tensions. As British authorities soon found out, the Intolerable Acts would become a uniting force as Patriots from all thirteen colonies came together to oppose the new laws.

The First North Carolina Provincial Congress

Although the Intolerable Acts and the Boston Port Act more specifically only affected Massachusetts, the punitive legislation motivated colonists with Patriot sympathies into action throughout North America. On August 25, 1774 seventy-one delegates representing thirty of North Carolina’s counties assembled at the Craven County Courthouse in New Bern. There they debated how to respond to the recent acts.

Called the Provincial Congress, this meeting was the first of its kind held in the thirteen colonies and, unlike the North Carolina Colonial Assembly, it wasn’t approved by royal authority. Later that year, several other colonies would hold their own provincial congresses to discuss principles of self-government. Calling the Boston Port Act a “most cruel infringement of the rights and privileges of the people of Boston,” North Carolinians resolved:

Until Parliament repealed the acts, the delegates resolved to boycott all imports from the East India Company, including tea. Further, unless “American Grievances” were addressed before October 1775, North Carolina would also halt all exports to Great Britain, including lucrative raw materials such as tar and tobacco. Calling for unity amongst the North American colonies, the delegates swore to only deal with those colonies who adopted similar boycotts in support of Massachusetts.

The Provincial Congress ended its meeting by electing three men to serve as North Carolina's representatives at the Continental Congress held in Philadelphia the following month. Like the Provincial Congress but larger, the Continental Congress hosted delegates from twelve colonies and wrote a petition to the King calling for a repeal of the Intolerable Acts. This body also later wrote and published the Declaration of Independence.

Photograph of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where most of the proceedings of the Continental Congress occurred. Courtesy of the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

The Edenton Tea Party Resolves

The North Carolina Provincial Congress’s resolves were published in local newspapers. News of the boycotts also came to Edenton via word of mouth when the local congressional delegates, including Frances Johnston’s husband Samuel, returned home. Throughout the month of October, women in Edenton and the surrounding area had their own debates about the Provincial Congress’s resolves, the Intolerable Acts, and about taxation without representation.

Ultimately fifty-one women decided to take a stand. Echoing the Provincial Congress’s resolves that Parliament’s treatment of Massachusetts was unjust, they wrote their own resolution agreeing to boycott the importation of British goods until parliament repealed the Intolerable Acts.

Rather than remaining anonymous, the women signed their names, showing the world that they would take accountability for their beliefs. Their resolves now stand as one of the earliest instances of political activism by colonial American women.

Read the historic document below.

The Edenton Tea Party Resolves signers would have written the original document by hand, using implements like those pictured here. Courtesy of Historic Edenton.

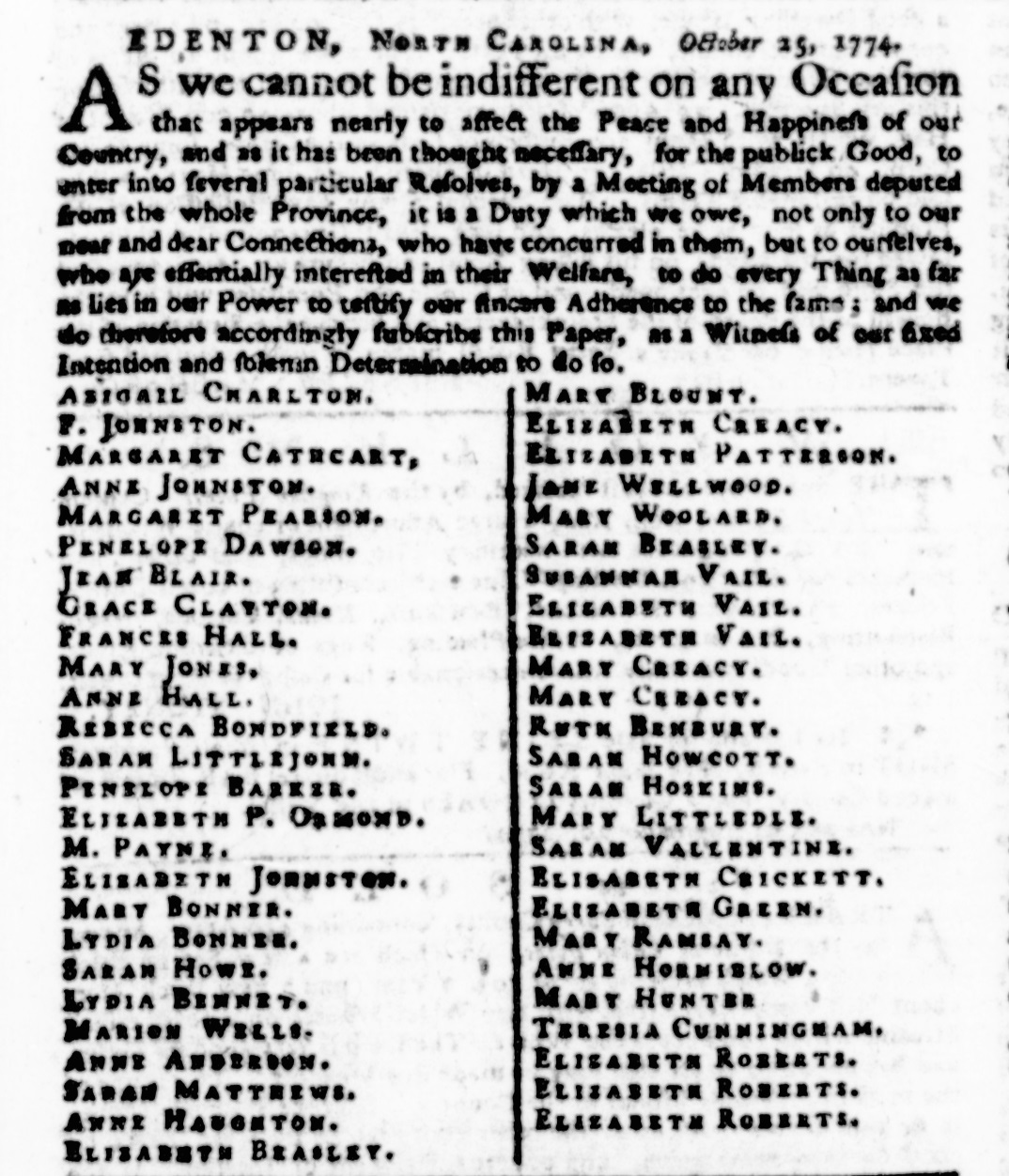

Earliest extant version of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves, printed in the postscript of the Virginia Gazette (pub. Purdie & Dixon) 3 November 1774. Courtesy of Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

EDENTON, North Carolina, October 25, 1774.

As we cannot be indifferent on any Occasion that appears nearly to affect the Peace and Happiness of our Country, and as it has been thought necessary, for the publick Good, to enter into several particular Resolves, by a Meeting of Members deputed from the whole Province, it is a Duty which we owe, not only to our near and dear Connections, who have concurred in them, but to ourselves, who are essentially interested in their Welfare, to do every Thing as far as lies in our Power to testify our sincere Adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this Paper, as a Witness of our fixed Intention and solemn Determination to do so.

- For more information about the Edenton Tea Party Resolves within the context of women's political activism through boycotts and the coming of the American Revolution, see Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1980); Ellen Hartigan-O'Connor, The Ties That Buy: Women and Commerce in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980); Cynthia Kierner "Edenton Tea Party Women," in North Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times, eds. Michele Gillespie and Sally G. McMillen, vol. 1 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2014), 12-33.

- For more information about the Boston Tea Party, see Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010); Benjamin Woods Labaree, The Boston Tea Party (New York, Oxford University Press, 1964).