The Papers of Arthur Dobbs: A Colonial Records Digital Edition

Arthur Dobbs (1689-1765) served as the Royal Governor of the North Carolina Colony from 1754-64. An Irishman by birth, Dobbs saw his adopted home through a period of immense upheaval. His term is marked by the French and Indian War, colonists' changing relations with American Indians, and Dobbs' frequent disagreements with the North Carolina Colonial Assembly.

The Papers of Arthur Dobbs

A Colonial Records Digital Edition

Introduction

Arthur Dobbs (1689-1765) served as the Royal Governor of the North Carolina Colony from 1754-64. An Irishman by birth, Dobbs saw his adopted home through a period of immense upheaval. His term is marked by the French and Indian War, colonists' changing relations with American Indians, and Dobbs' frequent disagreements with the North Carolina Colonial Assembly.

Keep Scrolling to Learn More

Dobbs by the Numbers

Dobbs' Most Common Recipient

Transcribed

Most Common Person Mentioned

The North Carolina-South Carolina Boundary

One of Governor Dobbs' major goals was settling the boundary between North and South Carolina.

As Dobbs arrived in the colony, he soon found that as white settlers moved onto lands in the western parts of North Carolina & South Carolina, they had frequent disagreements with the American Indians living there, and with one another another.

Dobbs claimed that the South Carolina government was secretly trying to take North Carolina land for themselves by issuing faulty land grants and called the SC land agents and sheriffs an "invasive force."

The disputed boundary also ran through Catawba and Cherokee lands. While South Carolina wanted to give those nations a 30-mile radius around their lands, Dobbs only wanted to grant them a 6 sq. mile area instead so that North Carolina planters would have more space.

In the end, Dobbs traveled to Augusta, GA in 1763, where he met with several southern governors and leaders from the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Catawba Nations. There they settled the disputed portion of the boundary, granting the Catawba a 15 sq. mile area.

Surveyors established a new western portion of the NC-SC boundary in 1764, but it wasn't until 2013 that the full boundary was finally settled.

Picture of the survey stones marking the boundary between North and South Carolina, courtesy of the NC Geodetic Survey.

Map of the boundary between North Carolina and South Carolina, indicating how the boundary went around the Catawba Nation.

The French and Indian War & the North Carolina General Assembly

Governor Dobbs' arrival in North Carolina coincided with the beginning of the French and Indian War in 1754 when the British learned that French fur traders were moving into a region of the Ohio Valley that England had claimed.

Dobbs recruited a group of North Carolinians to go on a military expedition under General Braddock to attack the French in the Ohio Valley. He sent the colony's recruits under the command of his son, Captain Edward Brice Dobbs.

French troops and their American Indian allies ambushed the British expedition at the Battle of Monongahela in July 1755, killing General Edward Braddock and igniting a large-scale war.

In response to the threat of a coming war, Governor Dobbs ordered the establishment of a fort on the colony's western frontier (now Statesville) called Ft. Dobbs, which is now a state historic site.

While there were never any major battles in North Carolina, Governor Dobbs often found himself at odds with the North Carolina Colonial Assembly about how many men they should recruit for the war effort and how the colony could pay them each year.

Picture of the modern reconstruction of Fort Dobbs, courtesy NC State Historic Sites.

In response to the King's demands for troops the Assembly questioned Dobbs, asking why should North Carolina raise troops to fight outside of the colony when they needed better security along their own frontiers? Moreover, troops were expensive and the assembly feared that they could pay the militia with costs for everything rising due to the war.

This tension between the assembly and Dobbs was major obstacle for the governor. In writing about the assembly, Dobbs often mentioned his "strong struggle" with them, how the representatives were "as obstinate as mules." He found some members "unreasonable and indecent" and even tried to have several colonial officers' dismissal for supposed misconduct, including John Rutherfurd and John Starkey.

Dobbs' term saw the colony through the rest of the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763. For North Carolina, the war had meant an economic downturn, frequent skirmished between western settlers and the Cherokee people, and partisan fighting between Dobbs and the Assembly. In the end, these struggles would contribute to the coming American Revolution.

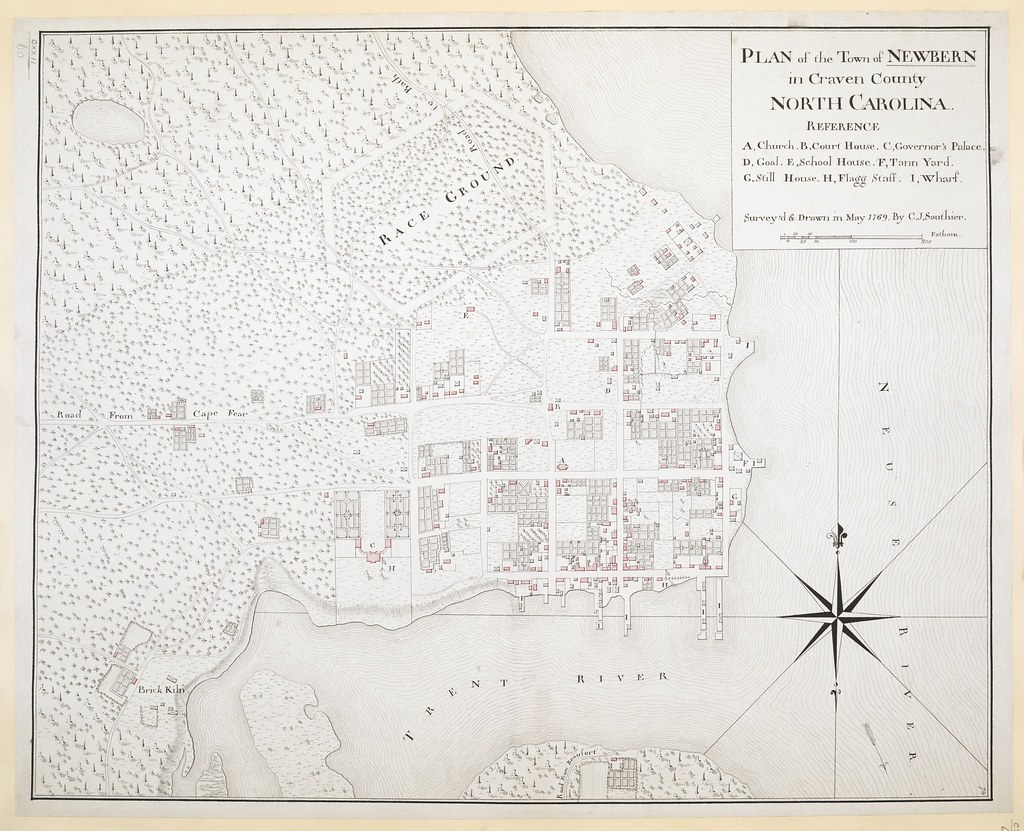

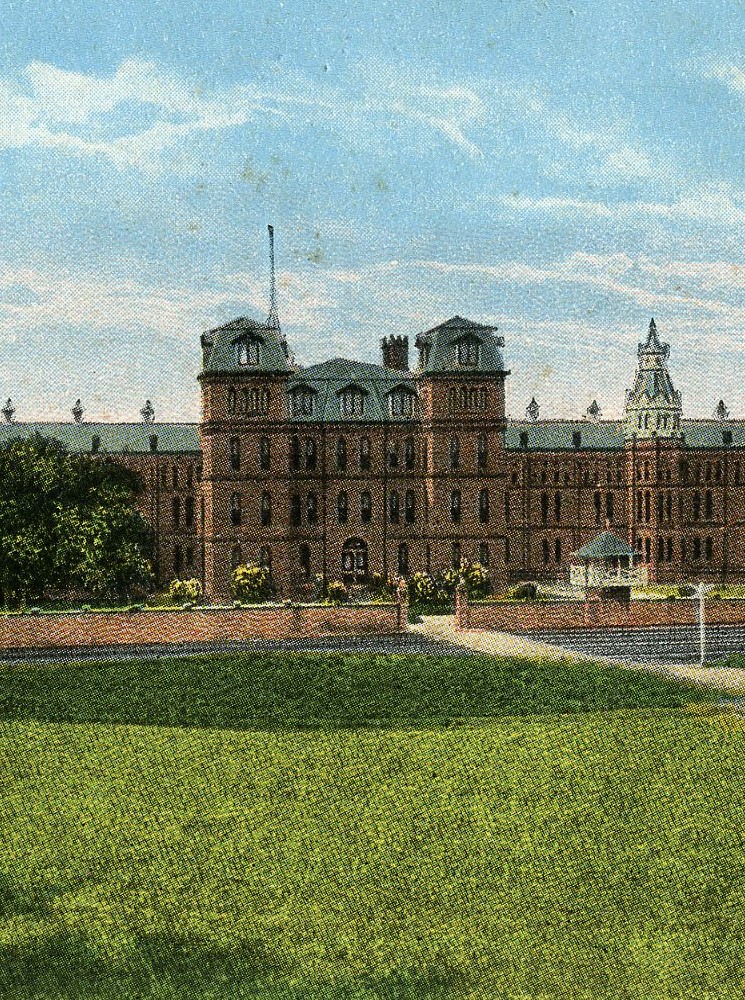

Map of New Bern, North Carolina, where the North Carolina Colonial Assembly frequently met.

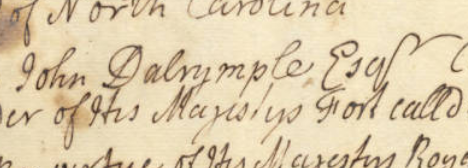

John Dalrymple

Detail of Arthur Dobb's Commission to John Dalrymple, 31 March 1755

One of the most notable military commissions that Governor Dobbs granted was to John Dalrymple as the Commander of Fort Johnston on the Cape Fear River.

Sometime prior to 1760, Dalrymple left his post and went to England without asking for Dobbs' approval, leaving the fort without a commander in wartime.

Dalrymple tried to come back to his post in 1762 and Dobbs ordered him under arrest for deserting his post. Dalrymple was a "Reptile," with "ill Character" Dobbs wrote, and claimed General Braddock had once said:

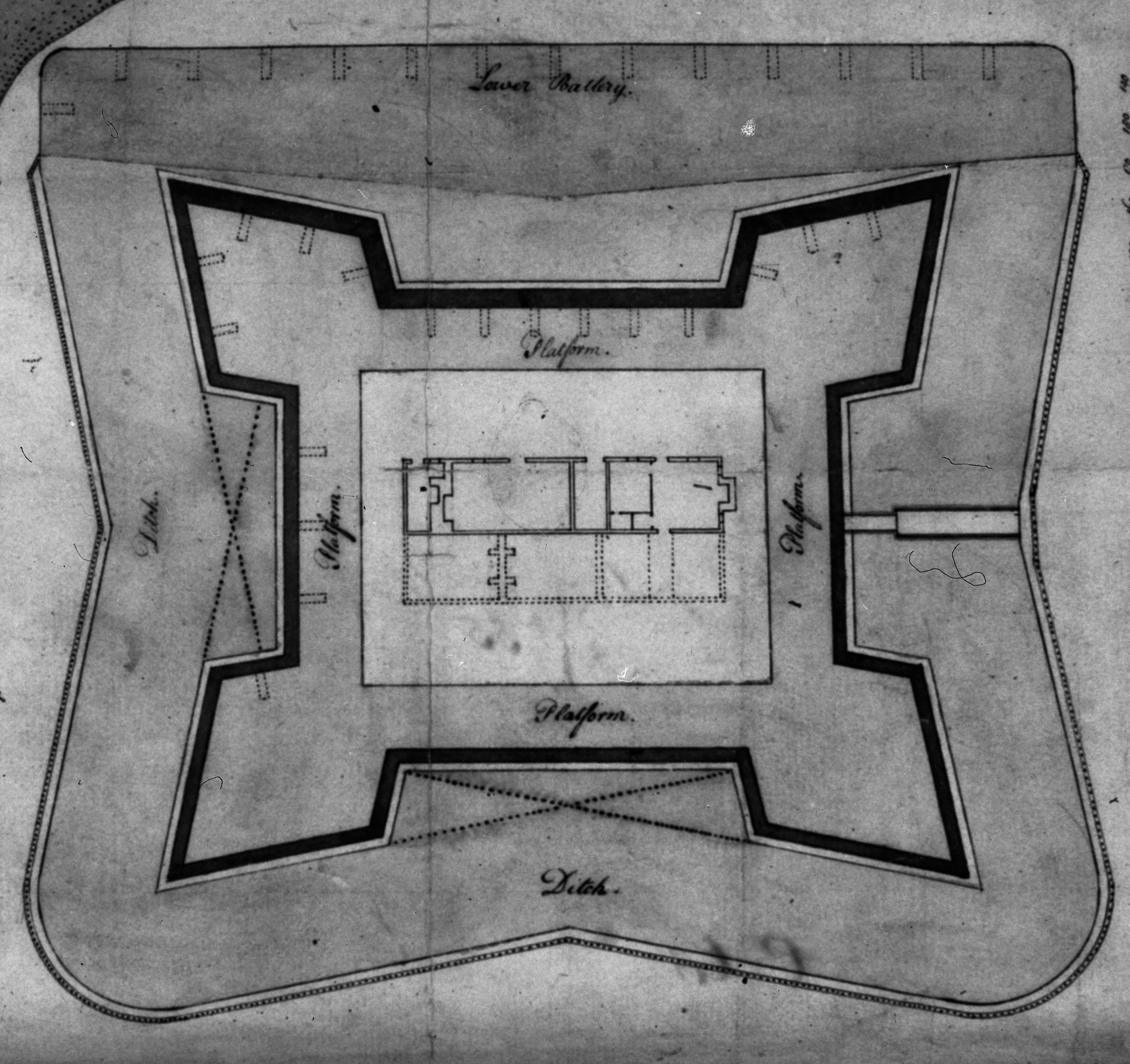

Diagram of Fort Johnston, where Dalrymple assumed command and was later imprisoned

While Jeffery Amherst, the Commander of all British forces in North America figured out what to do with him, Dalrymple stayed under arrest at Fort Johnston.

In February 1763, while under confinement, Dalrymple asked Michael Sissholt, the fort's new commanding officer, to come in his room and drink some punch with him. When Sissholt agreed, Dalrymple trapped him in the room and challenged him him to a duel, offering him a sword or a stick and proclaiming that either he or Sissholt "should die on the Spot."

Sissholt avoided the fight, but Dalrymple continued to be combative. That summer, while still under arrest, Dalrymple shot at the fort's new commanding officer, John Paine, through the window of his room.

By September, Dobbs ordered him to leave the fort and go under house arrest. Instead, Dalrymple left North Carolina altogether and went to New York, where Dobbs never heard from him again.

Personal Life

In his spare time, Arthur Dobbs enjoyed gardening, botany, and the natural sciences.

He explored the colony's countryside extensively and wrote several reports about his observations of North Carolina waterways, geography, climate, and soil.

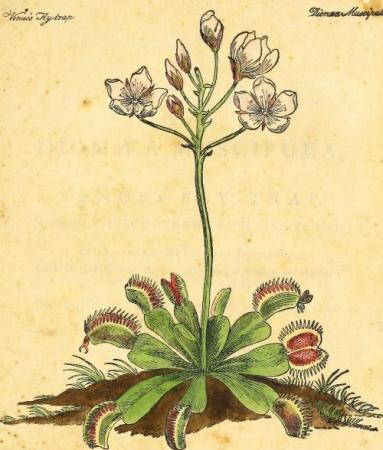

In 1759, Dobbs made the first known European observation of the Venus Flytrap, a plant unique to the Carolina Coast, which Dobbs called a "Catch Fly Sensitive which Closes upon any thing that touches it."

Due in part to Dobbs' discovery, the flytrap is now the official carnivorous plant of North Carolina.

Drawing of the Venus Flytrap plant by John Ellis, (1770), courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library

Dobbs, who had been widowed prior to his arrival in North Carolina, remarried in 1762 at Brunswick Town to Justina Davis, aged 15. She was 58 years his junior.

Despite the age difference, surviving letters about & from Justina indicate that the pair shared a mutual affection and upon his death, she wrote, "I have Lost one of the best and tenderest of Husbands."

After the Governor's death in 1765, Justina married Abner Nash, 2nd Governor of the State of North Carolina. She died in 1771 at age 26.

Justina Dobbs Nash's gravestone in the Halifax Colonial Cemetery, courtesy Historic Halifax

Nearing the American Revolution

Later photograph of the shipyard at Wilmington, where much of the colony's trade went through, courtesy State Archives of North Carolina

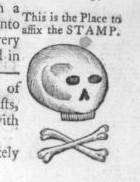

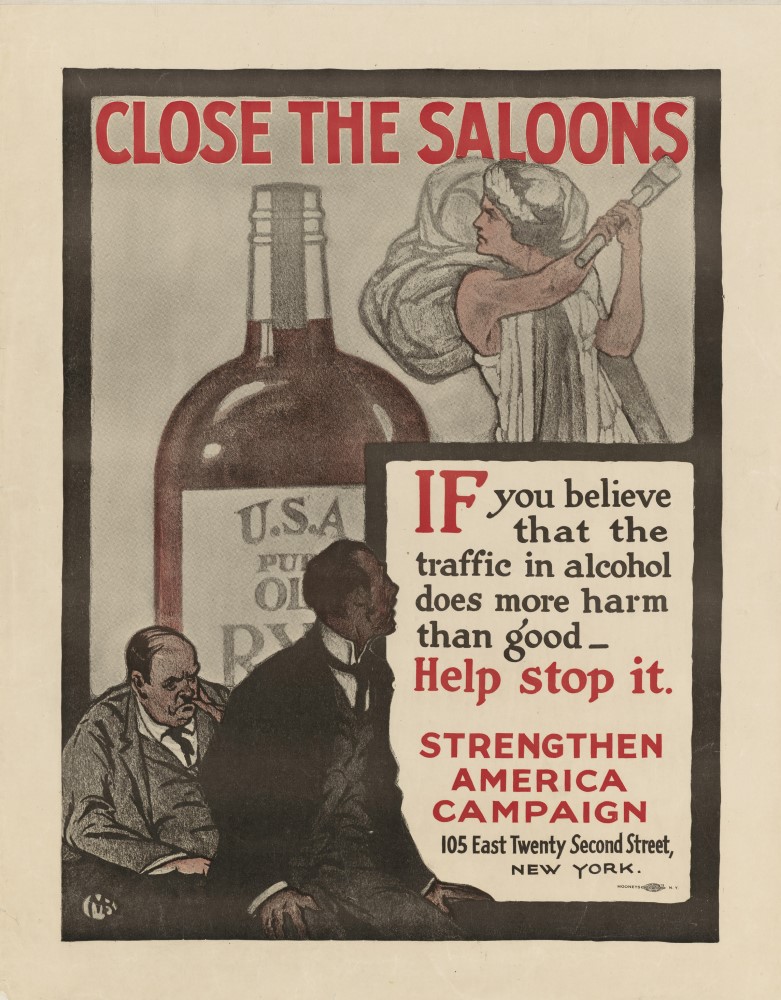

Art from a November 20, 1765 issue of the North Carolina Gazette protesting the Stamp Act, courtesy State Archives of North Carolina

Arthur Dobbs was a firm supporter of the King, but some issues he faced during his term were signs of the eventual American Revolution which would come a decade later.

Dobbs frequently found fault with colonial trade laws, which required British colonies to trade with England only, but not with one another. This law helped the English economy, but it made it hard for North Carolina's economy to develop. Dobbs urged the King to allow direct trade between NC and Ireland, but was refused.

Dobbs wasn't the only one frustrated. Many colonists grew increasingly upset about having to export their raw materials cheaply and in return having to buy manufactured good from Britain at high prices.

This trading system was by design, as it enriched England and kept colonies dependent, but colonists' feelings of exploitation in response to this system would be a factor in colonists' deciding to declare independence.

Another major sign of the coming revolution was one of the last acts that happened during Dobbs' administration: the Stamp Act.

Designed to help the British Treasury regain the money it lost fighting the Seven Years War, many colonists, including many in North Carolina, denounced the act as intolerable because they had not consented to the law.

Dobbs frequently fought with the Assembly about who had to right to make laws for the colony, was it the king or the people? Now, the Stamp Act Crisis heightened tensions between the Crown and the local Colonial government, putting colonists on a path towards revolution.

Conclusions

Citing poor health and a wish to settle his affairs back at home in Ireland, Dobbs was granted a temporary leave of absence from the governorship in May 1764.

Dobbs' replacement was William Tryon, who arrived in the colony in October 1764.

In March 1765 while preparing to leave the colony, Dobbs caught a cold and died, aged 75.

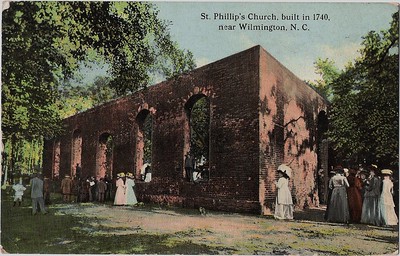

Dobbs was buried in St. Phillip's Church at Brunswick Town, not far from his home, survived by his wife Justina. Tryon assumed permanent governorship of the colony.

Exterior of St. Phillip's Church in Brunswick Town, where Dobbs is buried, courtesy State Archives of North Carolina