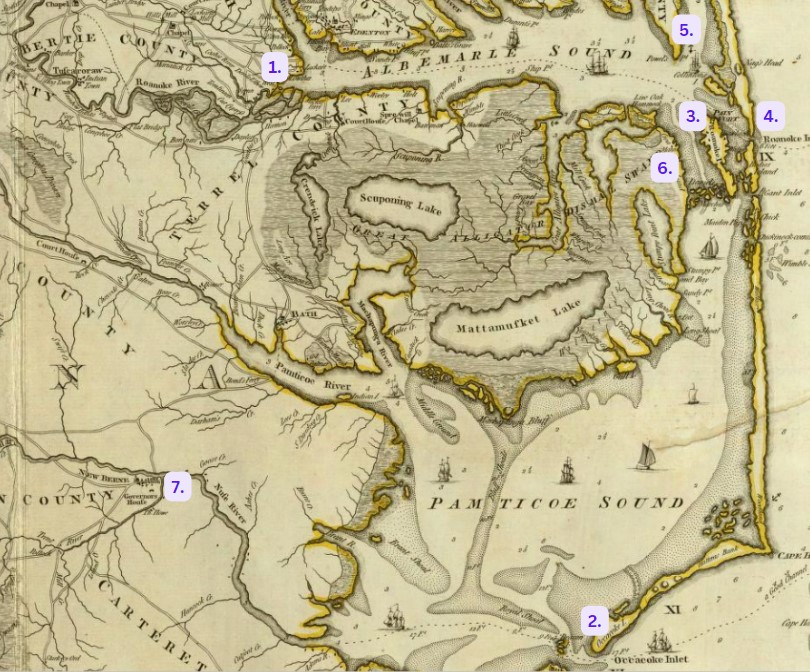

The Papers of Governor Locke Craig

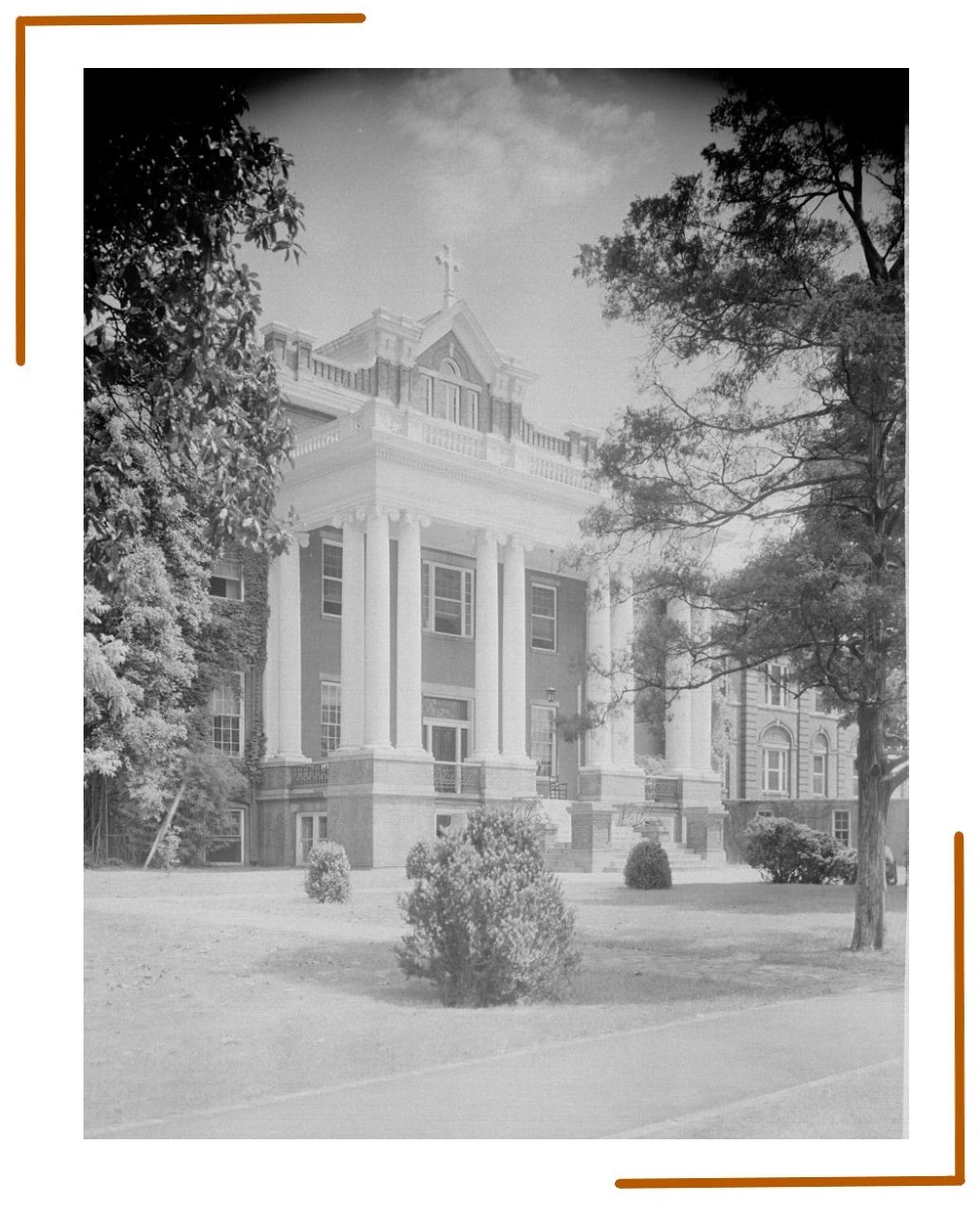

A selection of the papers of Governor Locke Craig, whose term in office spanned from 1913 to 1917.

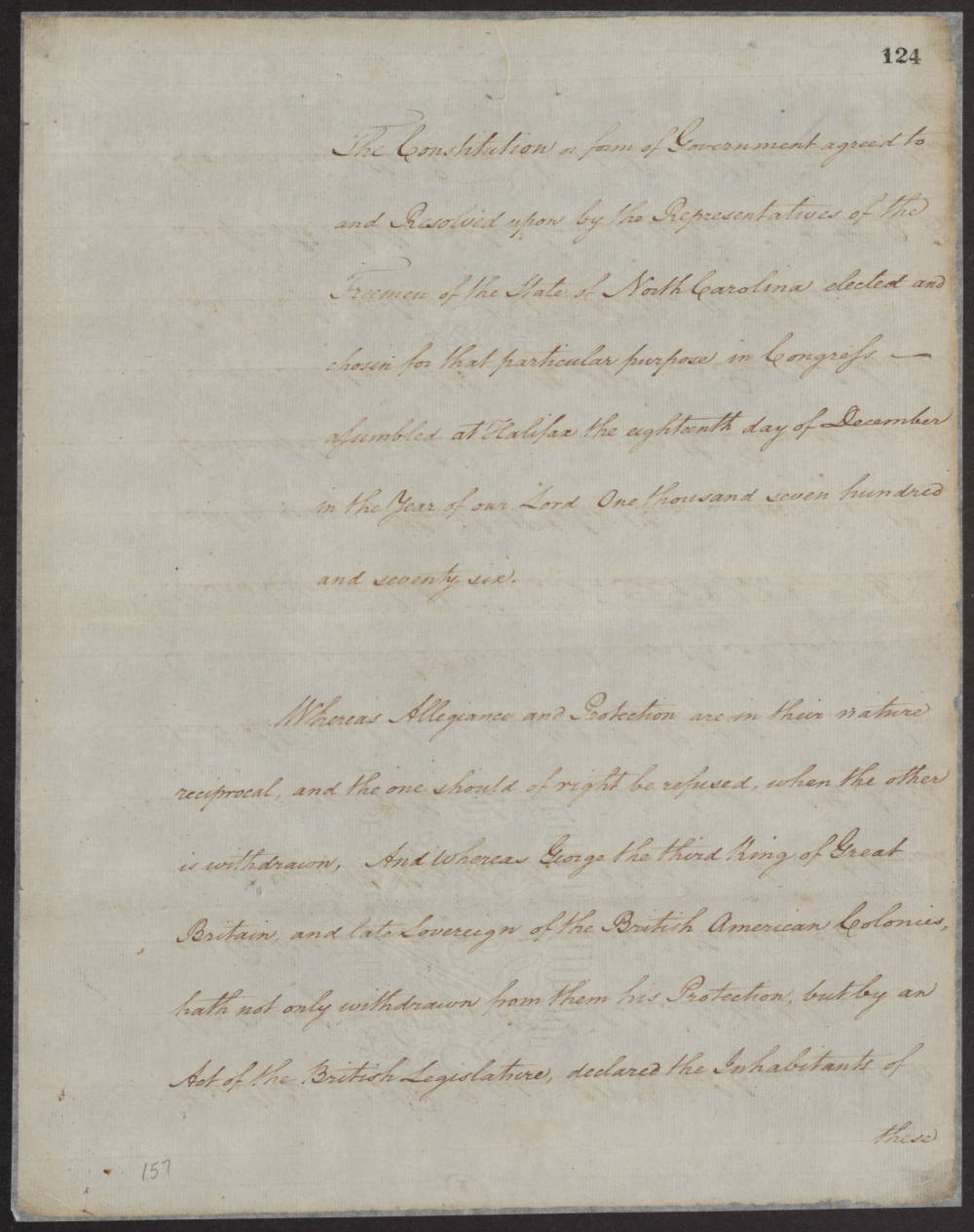

Source: State Archives of North Carolina, via Flickr.

The Papers of

Governor Locke Craig

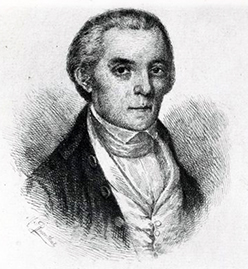

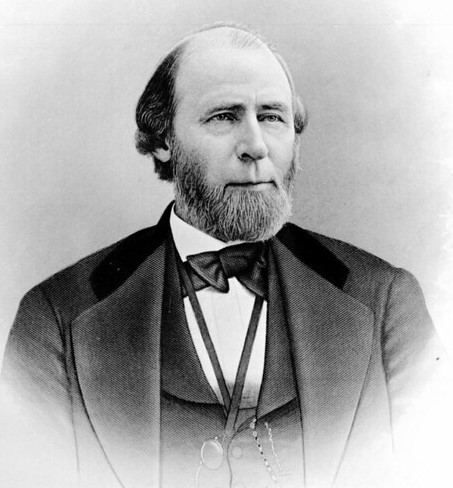

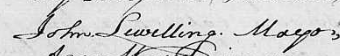

Known popularly in his time as the "Little Giant of the West," influential Asheville attorney and legislator Locke Craig rose to the governorship in 1913.

A Complicated Legacy

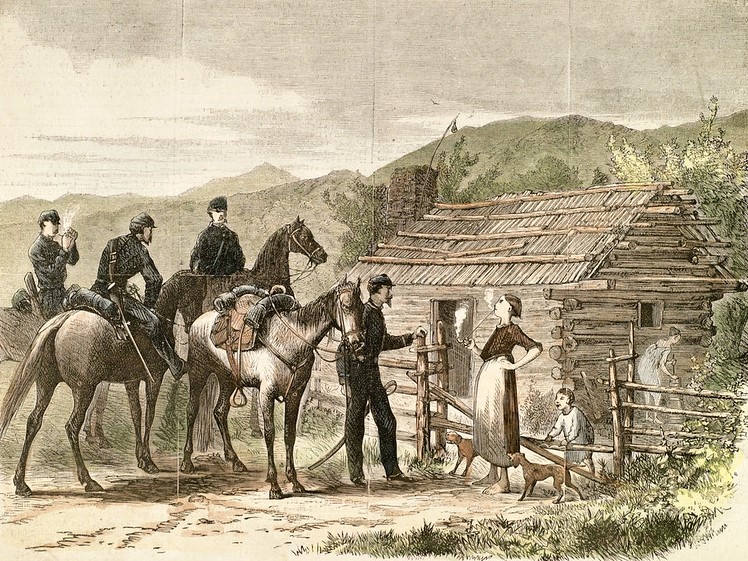

Slowed by chronic illness and heartsick for the mountain-etched skyline of his home in Asheville, perhaps no man was ever more prepared to end his term as governor than Locke Craig. From 1913 to 1917, Craig tirelessly navigated the state through the most pressing issues of his day: the building of a network of good roads, the creation of the State Park System with the conservation of Mount Mitchell, and the rebuilding of Western North Carolina following the 1916 flood, to name a few. His turn in the governor’s mansion saw great personal changes and challenges too—the deterioration of his health, the death of his close friend and executive secretary John P. Kerr, and the birth of his son, Locke Craig Jr., late in his own life.

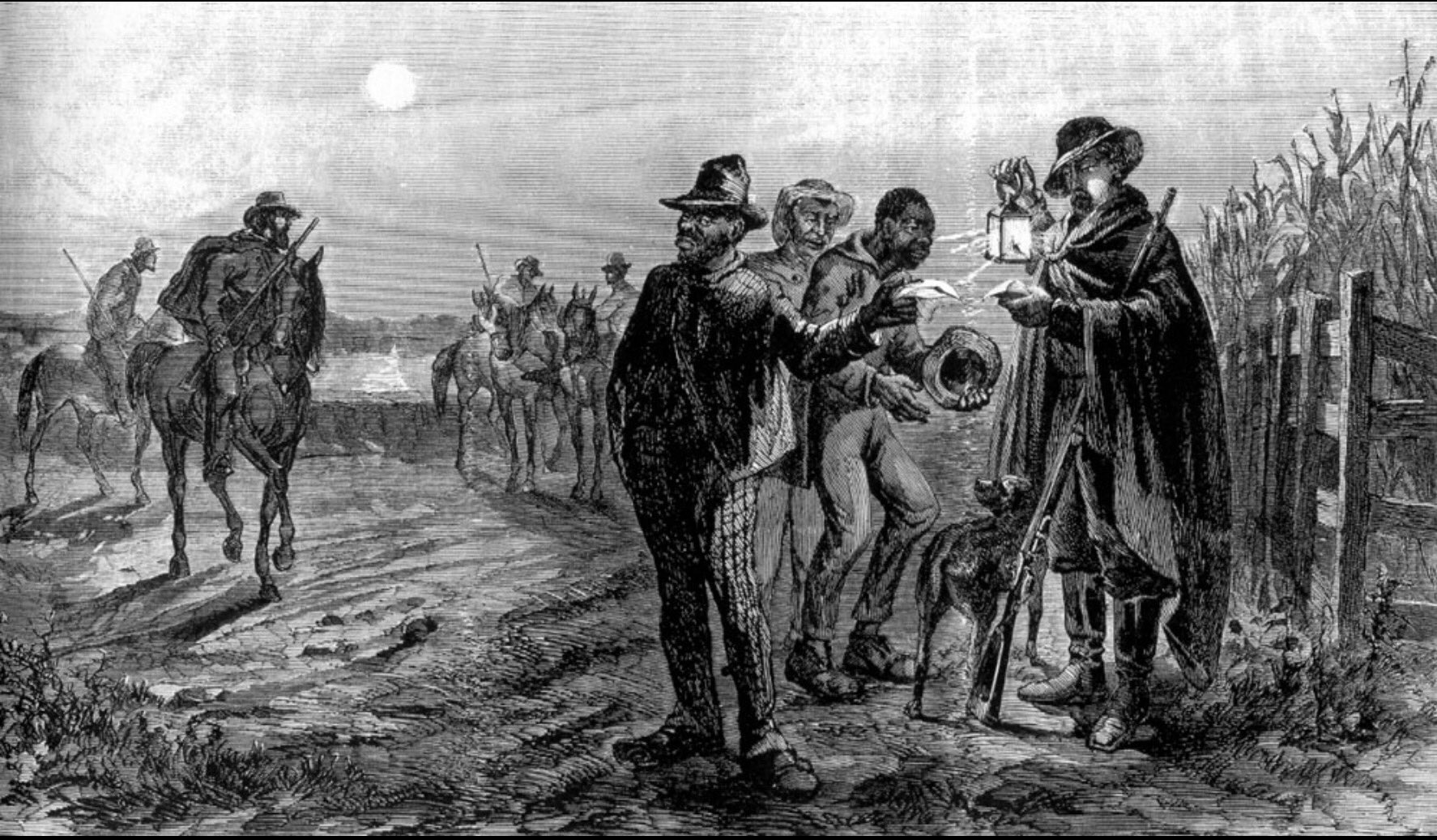

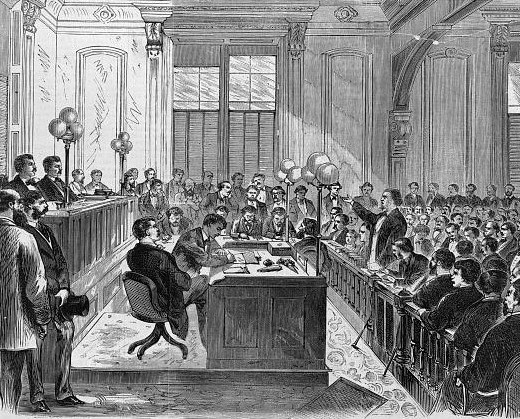

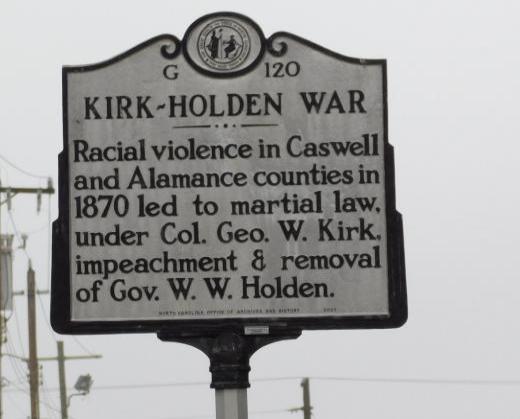

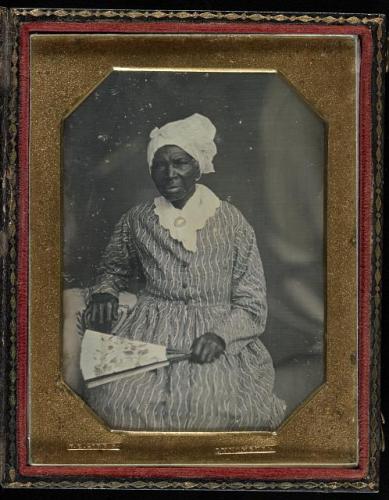

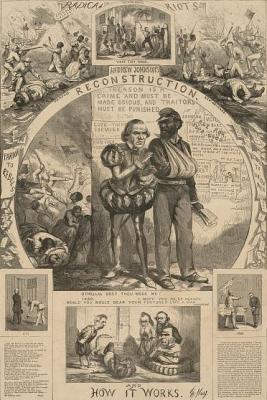

As much as we might admire Craig’s deft ability to triumph over complicated and lifechanging obstacles, we, as scholars of his political career, must also confront his unabashed dedication to the cause of white supremacy. It was Craig, after all, who stood shoulder to shoulder with Charles Aycock in launching the “campaign for the white man” at Laurinburg on May 12, 1898. Hitting the speakers circuit that summer with other prominent self-identifying white supremacists, Craig whipped white citizens into a racist frenzy. The bigoted fervor culminated in the violent murders of an untold number of Black North Carolinians and a suspension of Black voting rights that remained in place until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

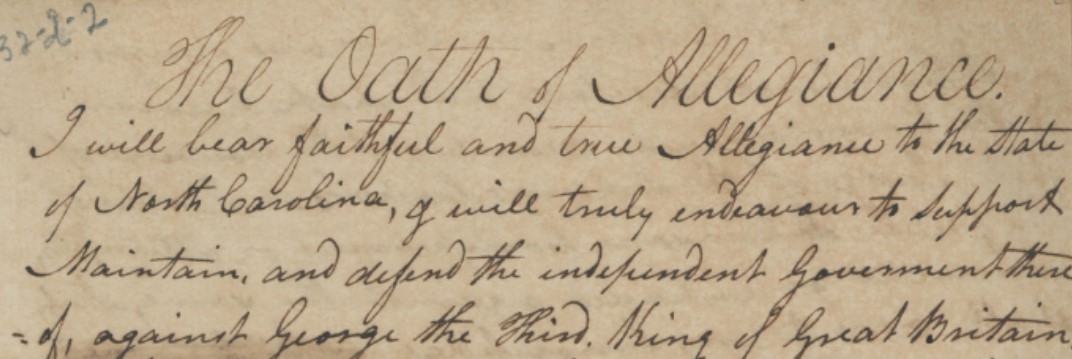

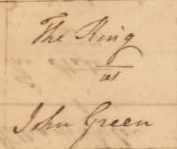

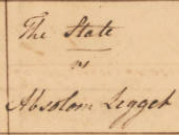

So, when placed in proper context, what are modern North Carolinians to make of Governor Craig’s legacy? The goal of this project is not necessarily to answer that question for today’s citizens and scholars, but rather to equip them with the primary sources necessary to examine his administration—and, more importantly, his words—for themselves. Over 500 transcribed and annotated documents shed light on the most significant themes of his time as governor.

.jpg)