Signers of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves

Signing one’s name to a public protest of the British government wasn’t a small act. Just as Massachusetts was punished for the events of the Boston Tea Party, it was possible that the women who signed the Edenton Tea Party Resolves might face harsh consequences as well when the British government heard of their protests.

The women who signed the resolves did so even though they had something to lose. The signers were not rash teenagers caught up in the moment. Instead, of the forty-five signers who have been identified, eighty-four percent of them were married. The average age of the signers was thirty-five years old. Only three signers were younger than twenty. For all these women, the decision to sign was likely a deliberate one, and one on which the women carefully weighed their options, thinking not only about their own political beliefs, but also the responsibilities that they owed to their spouses, children, and larger families and communities.

Outlined below are some snapshots of some of the more notable signers of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves. These brief biographies are not complete summaries of their lives but demonstrate the wide breadth of the signers’ backgrounds and experiences.

Average Signer's Age

The Orchestrator?: Penelope Barker (née Padgett)

Whether Penelope Barker truly was the organizer of the resolves or not, it’s clear that she certainly had the leadership skills and organizational capacity to do so. At the time of the signing, Penelope Barker’s husband Thomas had been away for thirteen years, working most of that time as an agent for the colony’s interests in Britain. Though the Barkers maintained a correspondence, Penelope was responsible for the day-to-day management of their property.

Moreover, her husband’s absence was by no means the only hardship Penelope had faced in her life. At age seventeen she lost her sister Elizabeth and subsequently married Elizbeth’s widow John Hodgson, becoming the stepmother to her three nieces and nephews. Just two years later John Hodgson died, leaving Penelope, still a teenager, with five children to care for. Penelope was widowed a second time in 1755 when her next husband James Craven died. By the time of the signing in 1774, Penelope had borne the loss of not only two husbands, but also all five of her biological children.

After the resolves’ signing, Penelope’s husband Thomas finally returned home in 1778 after having escaped Britain via France. The couple later built a house together which still stands at the Edenton waterfront as the welcome center for the Edenton Historical Commission.

Illustration from Within Our Power: The Edenton Ladies' Tea Party decpicting Penelope Barker signing the resolves. Courtesy of Jonathan D. Voss.

The Noble: Margaret Duckenfield Pearson (née Jolly)

Margaret Jolly was likely born in Lancashire, England in 1719. At age twenty-three, she attracted the attention of Nathaniel Duckenfield, an aristocrat from Cheshire who was nearly her father’s age. Duckenfield had extensive landholdings in England, but also importantly he maintained a plantation near Salmon Creek in Bertie County, North Carolina. Through this connection, Nathaniel had worked as an agent and advocate for the colony during the 1720s.

Margaret and Nathaniel married in 1745 and a year later their son Nathaniel Jr. was born. When Nathaniel Sr. died in 1749, Margaret assumed ownership of the family’s property and in 1756 she arrived in Bertie County to take over the plantation there, called Duckenfield. By the 1760s Margaret had settled permanently in North Carolina and married John Pearson, a lawyer. Margaret’s fortunes improved again when her son Nathaniel Jr. became the Baronet of Dukinfield in 1768. Although Margaret was firmly attached to North Carolina, her son’s aristocratic title tied him to the other side of the Atlantic and he returned to Britain in 1771.

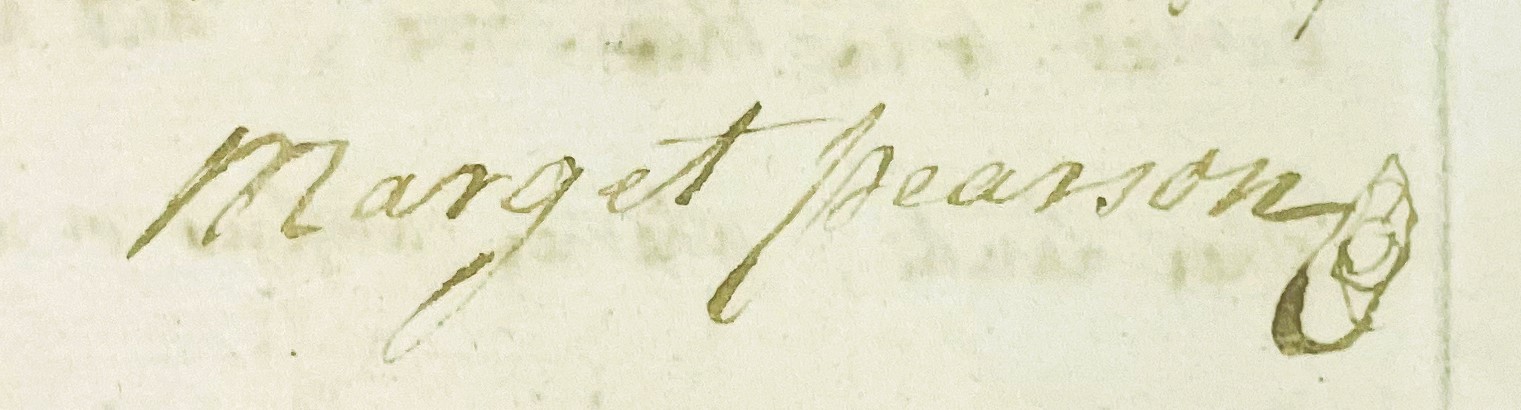

Margaret Pearson's signature, taken from her will. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

As the American Revolution neared, questions of allegiances put a strain on colonists like Margaret who still held tangible ties to Britain. In 1774 she was among the first signers of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves. Just a year earlier however, her son Nathaniel Jr. had become an officer in the British Army. Perhaps out of respect for his mother’s political leanings, he became an adjutant in 1775, but only on the condition that he never be forced to serve against American forces. Regardless of his own politics however, the State of North Carolina still considered Nathaniel Jr. a loyalist and in 1778 they confiscated his property. Trying to defend her son and maintain the family’s wealth, Margaret unsuccessfully petitioned the state to get his land back.1 Despite the setback, Margaret remained in North Carolina, and she died at the Duckenfield Plantation in 1784.

The Governor's Heiress: Penelope Dawson (née Johnston)

Penelope Johnston was perhaps one the most unlikely signers of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves. Several of her cousins were also signers, but she, unlike them, was the daughter of formal royal governor of North Carolina Gabriel Johnston. Penelope’s ties to the British establishment did not stop there either. Her grandfather was Charles Eden, another colonial governor, and through these connections Penelope became an heiress to an immense fortune.

When Penelope was orphaned at age eleven, she fell under the guardianship of Virgina’s governor Robert Dinwiddie. Spending time in both Edenton and Williamsburg, Penelope enjoyed a cosmopolitan lifestyle and was unusually highly educated compared to her peers. This is all to say that Penelope’s fortunes were intensely tied to the British Empire.

Despite these ties however, Penelope also had a bit of a rebellious streak. In 1758 she had eloped with John Dawson, a young surveyor from Virginia. Her family initially was shocked by the match, but they eventually came around and the couple settled at Eden House, Governor Eden’s former estate, in Bertie County. There, when the time came in 1774, Penelope Dawson signed the Edenton Tea Party Resolves and firmly affixed her name to the protest of Great Britain’s policies.

Illustration from Within Our Power: The Edenton Ladies' Tea Party depicting a Penelope Dawson with a parasol. Courtesy of Jonathan D. Voss.

The Churchwarden's Daughter: Anne Hall

Anne Hall was one of the younger signers, aged just twenty years old. Unlike the vast majority of the signers, Anne was unmarried, and given her signature’s placement on the document, she likely followed her mother and older sister Mary in affixing her name.

The Halls were a notable family in the area. Anne and her sister Mary were two of the family’s nine children born out of the union of Clement Hall and Frances Foster. Clement, an Anglican missionary, was also the author of the first non-legal text published in North Carolina, a collection of poems. He died unexpectedly when Anne was just four years old, leaving her mother Frances to manage the large household on a diminished income. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel no longer supported the family following Clement’s death, and it’s possible this soured the Halls toward British policy. Whatever the reason, Anne, her mother, and two of her sisters signed the resolves.

The family’s support of the evolving Patriot cause didn’t stop there either. Not only was Anne’s brother Clement Jr. an officer in the Continental Army, but Anne herself married the colonel of the Chowan County Regiment of the North Carolina Militia, James Blount.

Photograph of Mulberry Hill, the plantation in Edenton where Anne Hall Blount spent most of her adult life. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

The Tavernkeeper: Anne Horniblow (née Rombough)

One of the last signers of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves was Anne Horniblow (née Rombough). A lifelong resident of Chowan County, Anne came from a family of skilled craftspeople. Her father John Rombough was a joiner and cabinetmaker, and two of Anne's brothers also followed him into woodworking. When she was about eighteen, her parents arranged for Anne's marriage to John Horniblow, the proprietor of one of Edenton’s local taverns. The Horniblows’ marriage may not have been a happy one, at least at its outset. When they married in November 1772, the town gossip was that Anne “was averse to the Match, & forced to it by her Father & Mother.”2

As Mrs. Horniblow, Anne likely worked in the tavern alongside her husband, keeping drinks filled, the floor swept, and fires stoked. There Anne surely overheard many political debates of the day, such as questions of taxation without representation and the balance between royal authority and democracy. On these political questions, Anne sided with the Patriots. In 1774, aged about twenty, Anne Horniblow signed the resolves and pledged to support the colonial boycott movement. Sources suggest Anne’s decision to sign the agreement had her family’s full support. Not only did her husband sign an oath in support of the American government during the later Revolutionary War, but Anne’s father was a member of the Edenton Committee of Safety, an early form of Patriot governance which enforced the boycotts.

Illustration from Within Our Power: The Edenton Ladies' Tea Party depicting Anne Horniblow working at her family's tavern. Courtesy of Jonathan D. Voss.

The Colonel's Daughter: Elizabeth Johnston (née Williams)

Elizabeth Williams was born in North Carolina in 1751 and married John Johnston in about 1767. Their union marked a melding of two important political families in northeastern North Carolina. Elizabeth’s father, William Williams, had represented Bertie County in the North Carolina Colonial Assembly. By the time Elizabeth signed the Edenton Tea Party Resolves, her husband John was serving in the body as well. Perhaps spurred on by her support of the boycott agreement, both her father and husband later served as delegates to the North Carolina Provincial Congress.

By the outbreak of the American Revolution, Elizabeth’s family’s patriotic fervor had not diminished. John served as the clerk of the Bertie County Court, where he swore local citizens’ allegiance to the State of North Carolina. Meanwhile her father was a colonel in the Martin County Regiment of the North Carolina Militia.

Detail of Martin County on an 1808 map of North Carolina. The map indicates the location of Williamston, named for Elizabeth's father, and the Johnston residence, where her family lived. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

- Petition of Margaret Pearson, 8 January 1779, in The Papers of James Iredell, 1778-1783, ed. Don Higginbotham (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, 1976) 60-1.

- James Iredell, "The Diary of James Iredell, 1770-1773," in The Papers of James Iredell, 1767-1777, ed. Don Higginbotham (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, 1976) 183-4.