Free Women of Color during the American Revolution

Contrary to our understanding of military policy in the 18th century, North Carolina's Patriot army was an integrated force. White men and free men of color served alongside one another with no distinction in pay or status.1 Prior to North Carolina revising its state constitution in 1835, all free adult men, regardless of race, were subject to the draft.2 The notion of the Patriot army in North Carolina being bureaucratically colorblind was so firmly entrenched that payrolls, discharges, and other military documents seldom made note of a soldier’s race. In many cases, it is only when veterans and their families later went to apply for a pension that primary sources actually indicate the soldier's racial identity.

While states such as South Carolina banned people of color from serving in the army and other states such as Rhode Island segregated their units, it was within the norm and was in fact expected for North Carolinian men to serve alongside one another. Some enslaved men served in the military as well, sometimes as a substitute for their enslavers or as part of an agreement that they would be freed for their service, though this was less common.3

Just as free men of color served in the American militiary, free women of color also made many sacrificies to keep their homes and families together during the war. Two such North Carolinians are Rachel Pettiford Locus and Nelly Evans Taburn.

"She is the Widow of Valentine Locus, who was a private Soldier in... the Revolutionary War"

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Rachel Locus, 24 May 1838

"That she is the Widow of William Taburn Sr. who was a private in the No. Carolina Militia"

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Nelly Taburn, 26 May 1845

After the war, the Locuses, Taburns, and many other veteran families of color collected their bounty lands to which all veterans were entitled. However, despite their many contributions to the war effort, free people of color faced a mounting level of discrimination as time went on. Free women of color had never been allowed to vote, and the white delegates of the North Carolina Constitutional Convention revoked free men of color's voting rights in 1835. Moreover, though they had a right to petition the legislature, they could not testify in court against their white peers. This restriction posed an issue for many free people of color in their lives. For the Locus family, it meant they could not bring a suit against the white men who assaulted them and tried to kidnap and sell their children into slavery. These widows' stories are a testament to the many struggles free women of color in North Carolina had to overcome during the era of the early republic.4

Engraving of an African American woman. People of color participated in the American Revolution in ways similar to their white peers, whether as soldiers, farmers, or nurses. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

North Carolina Widows in Their Own Words

Keeping the Family Together: Rachel Locus

Despite Rachel Locus' identification as a free woman of color, her experience during the American Revolution was likely very similar to that of her white neighbors. For two years while her husband was away serving as a private in the Continental Line, Rachel cared for the children, grew crops, and managed their homestead. After her husband returned home, the Locuses eventually settled in Wake County, near Lick Creek.

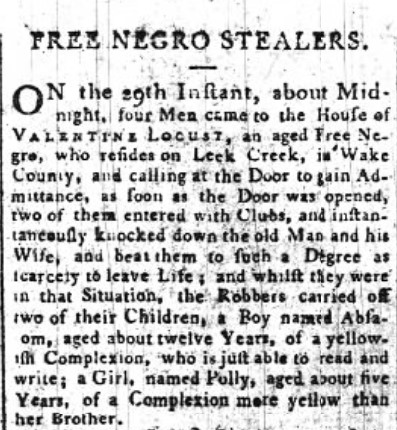

The many struggles Rachel faced in her life only compounded after the American Revolution. One night in 1801, a group of white men burst into her home and abducted two of the Locus children, Absalom and Polly. During the invasion, the men also violently assaulted Rachel and her husband Valentine, "to such a Degree as scarcely to leave life."

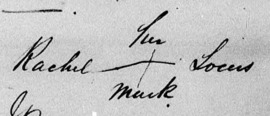

Rachel Locus's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

Article from the Weekly Raleigh Register, October 6, 1801.

The abductors likely intended to bring the children into the Deep South and sell them into slavery despite their status as free people of color. Even if they knew the kidnappers, the Locus' status as free people of color meant that they could not testify against the white criminals. Thankfully, after a tense night, Absalom and Polly were able to escape from their captors and find their way back to their parents' homestead. Sources indicate the criminals were never identified or charged for their crime. Rachel and Valentine appear to have made a full recovery following the assault. Still, the incident demonstrates how tenuous the Locus family's grip on freedom was.

After Valentine died in 1811, Rachel continued to raise her family of eight on her own. In 1838 she applied for a Revolutionary War widow's pension. After obtaining letters of support and other forms of proof of both her marriage and her husband's military service, Rachel's claim was approved. The difficulties of obtaining her pension did not stop there, however. In 1839 she wrote a letter to the Secretary of War, explaining that her pension agent, Thomas Edwards, had been collecting her pension on her behalf and keeping it for himself, effectively scamming her of her pension benefit. It was only when the federal government interceded on Rachel's behalf that she finally received the just entitlement of her claim as a Revolutionary War widow.

Struggle for Recognition: Nelly Taburn

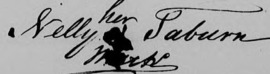

Nelly Taburn's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

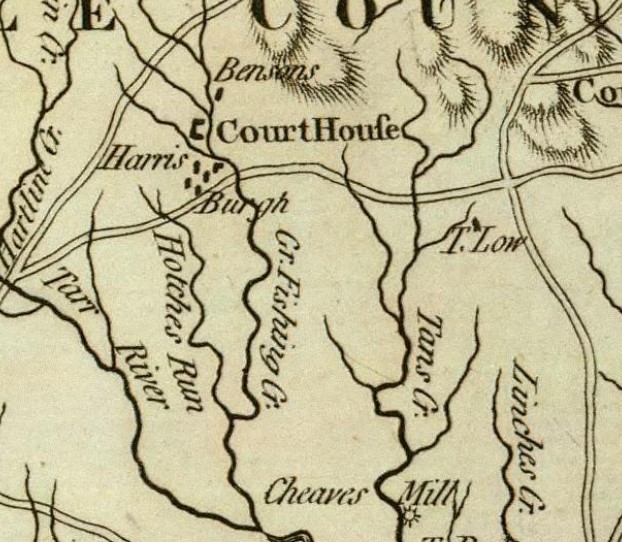

Twenty-four-year-old Nelly Taburn was living in Granville County when the revolution started. Born free people of color, Nelly and her husband William participated in the war just as their white neighbors did. William was drafted for three separate terms of duty, spending over ten months away in service during the war. While William was away, Nelly grew crops and managed the growing Taburn family on their tract near Fishing Creek.5

When it came time for William (and later Nelly) to apply for a Revolutionary War pension, his application faced additional scrutiny which those of his white peers did not. Simply put, the U.S. Pension Commissioner did not believe that an African American man could have served along white soldiers during the war. It did not matter how many glowing affidavits of support the Taburns collected from officers and other soldiers Taburn served with, it was unfathomable to the commissioner that the North Carolina Militia was an integrated force. It was only after North Carolina's Secretary of State verified that free people of color were subject to the draft during the war that the Taburns' claim was processed successfully.

Nelly likely suffered many hardships as she aged. By the time William applied for a pension, he was "almost blind" and living in the county poorhouse, meaning that Nelly was unable to rely on him for support. After her husband's death in 1835, she likely lived with one of her children or another family member, as she does not appear on the 1840 census.

1776 Mouzon map indicating the location of Fishing Creek in Granville County.

- It is important to state that despite the colorblind nature of North Carolina's Revolutionary-era forces, people of color still faced a great deal of additional scrutiny because of their race. Although white and free African American men experienced equal treatment as privates, African American soldiers were far less likely to be promoted in rank, let alone receive officer's commissions. For more information about Black men's experiences in North Carolina as part of the Patriot army, see W. Trevor Freeman, "North Carolina's Black Patriots of the American Revolution," MA Thesis, East Carolina University, June 2020 https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/handle/10342/8572 (accessed 2 January 2024). For Black Patriots at large, see Judith L. Van Buskirk, Standing in Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017); Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Gary Nash, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press, 2006); Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: 1961); William Cooper Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855).

- Free men of color were briefly barred from enlisting in the North Carolina Militia in 1812. The law was repealed in 1814 and free men of color did serve in the state militia once again, albeit in segregated units or columns. Warren E. Milteer Jr., North Carolina's Free People of Color, 1715-1885 (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2020) 56-7.

- Pension records suggest that a little over 400 men of color served in North Carolina Patriot forces. A larger amount may have served in the British army or used the war as an opportunity to self-emancipate. Freeman, "North Carolina's Black Patriots of the American Revolution," MA Thesis, East Carolina University. One enslaved North Carolinian who won emancipation due to his military service was Ned Griffin. See Jeffery Crowe, Black Experience in Revolutionary North Carolina (Raleigh: North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1977) 100.

- For the case study of another free woman of color from North Carolina who struggled to obtain a widow's pension, see Damani Davis, "The Rejection of Elizabeth Mason: The Case of a 'Free Colored' Revolutionary Widow," Prologue Magazine (Summer 2011) 43:2 https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2011/summer/mason.html (accessed 4 January 2024).

- Granville County Land Grant Files, State Archives of North Carolina, S.108.718, No. 115, Frame 1115 https://nclandgrants.com/frame/?fdr=390&frm=443&mars=12.14.66.1178 (accessed 3 January 2024).