In the late morning hours of January 6, 1921, Thomas W. Bickett peeled himself from the comfort of his bed and dressed for his final trip as governor from the Executive Mansion to the State Capitol. Shortly before noon, he took his place at the dais in the House chamber, and in a booming, determined voice greeted the “Lady and Gentlemen of the General Assembly.” Members of the press took note of his drastic change in appearance. In the course of the four years of his administration, Bickett's hair had conspicuously transformed from a healthy salt and pepper to a stark white. He didn’t look frail or fragile, per se, but just substantially older than the spry man who first arrived for inauguration four Januaries prior. Perhaps it was the illness he was then fighting. Or perhaps the trying years of World War I had ground him up a bit.

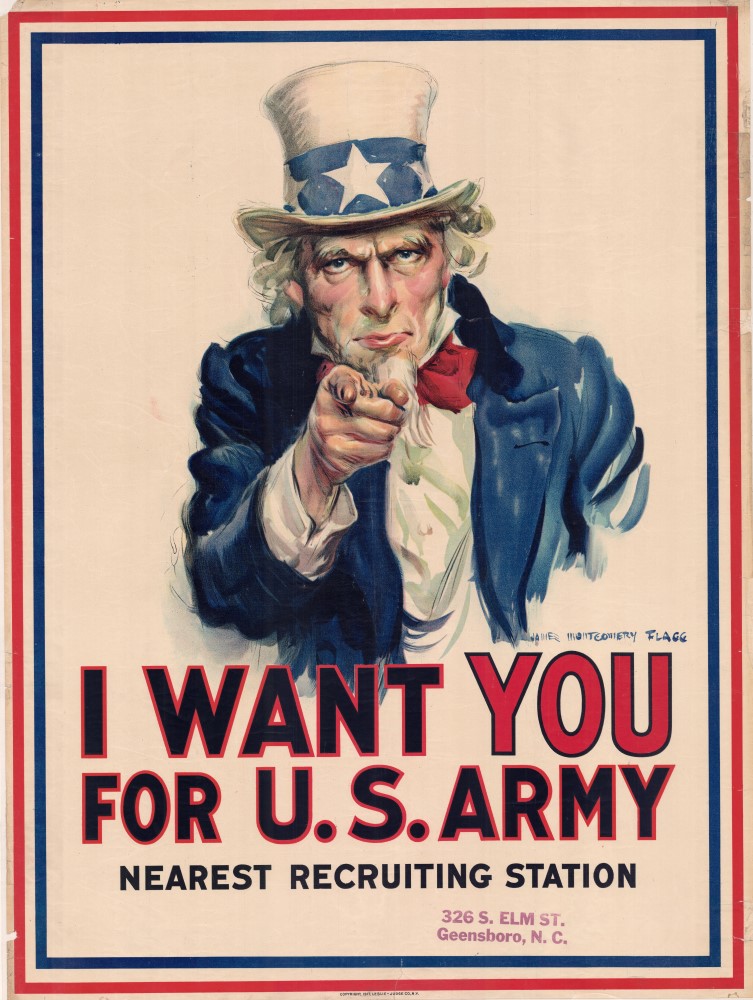

Bickett had, after all, put in place the administrative machinery that sent more than 2,300 men to their wartime deaths. Thousands more returned to North Carolina “shell shocked” and struggled to rejoin their communities. These sacrifices were not lost on Bickett, the son of one Confederate veteran, the son-in-law of another. Though he had publicly lauded the state’s role in the world war, Bickett's personal thoughts about his own public service during that same time might never be known. No historian or archivist has yet managed to turn up a journal or even much in the way of personal correspondence that might provide some insight into Bickett’s intimate feelings on the matter.

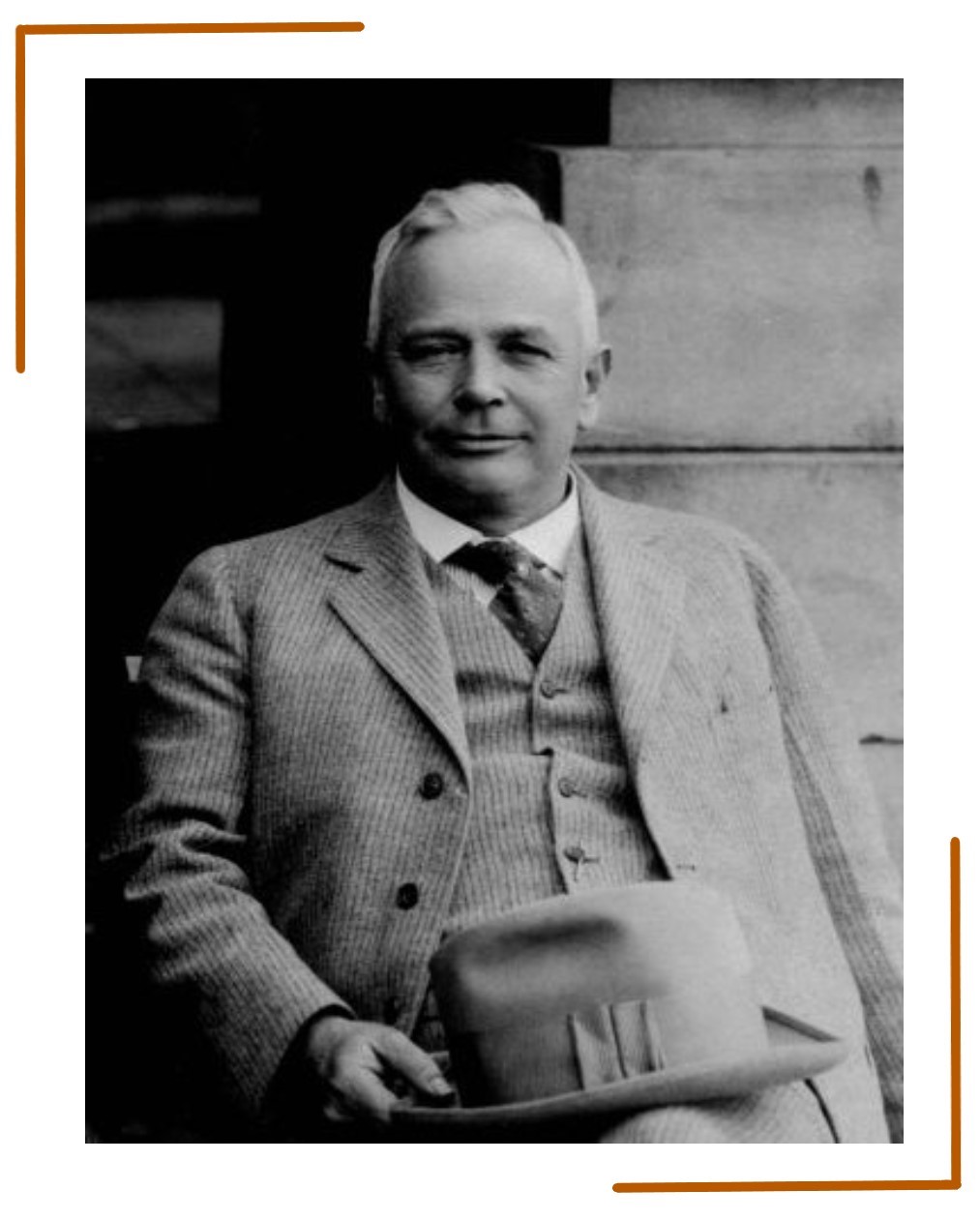

Governor Thomas W. Bickett, circa 1921. Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina.

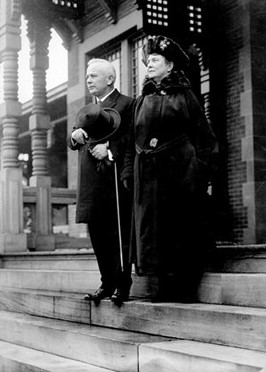

Governor Thomas W. Bickett and his wife Fannie Yarborough Bickett on the last day of his administration, January 6, 1921. Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina.

Other issues, too, had each taken their pound of flesh. Lock outs and strikes ground manufacturing to a halt, the confrontations between capital and labor often turning violent. White North Carolinians continued their campaign of racial terror, lynching seven Black men—including a war veteran in uniform—and garnering national criticism of both the state and its chief executive. The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 claimed the lives of an estimated 13,000 state citizens, leaving not a single community unscathed. The movement for women’s suffrage advanced rapidly, galvanized by the war’s societal restructuring, threatening to split his party in two. Nothing had come easy for Bickett, who, by the end of his term, seemed to wear the stress of it all like a wet wool cloak he could not shake from his shoulders.

Nevertheless, there he stood, one last time, before the legislature—noticeably older and quietly ill. Looking out over the gathered assembly, which for the first time included a woman, Bickett made known his lack of interest in celebrating his own accomplishments. “I do not propose to review my own administration,” he declared to the hushed crowd. “What is written is written, and will, in the fullness of time, be fairly appraised by the calm judgment of history.” For the Monroe-schoolboy-turned-Louisburg-lawyer, it was important that humility, above all else, characterize the closing chapter of his political career.

He could not have known then, standing there, a little tired, a little sick, that he would return to the Capitol just eleven months later—to lie in state. Any hope that he might run for United States Senate or any political office beyond that of the governorship had officially come to an end when Bickett breathed his last, shortly after Christmas Day, 1921. At once the champion of betterment for the people of North Carolina and also the defender of well-entrenched societal norms governing race, class, and sex, Bickett leaves behind him a complicated legacy that blurs the line between progressivism and conservatism. What results, for modern scholars of Bickett’s administration, is a unique and at times confounding convergence of old south and new, tradition and modernity, progress and stagnation.

Identified

Transcribed

Most Mentioned Person