The Diary of Margaret Eliza Cotten

Who is Margaret Elizabeth Cotten?

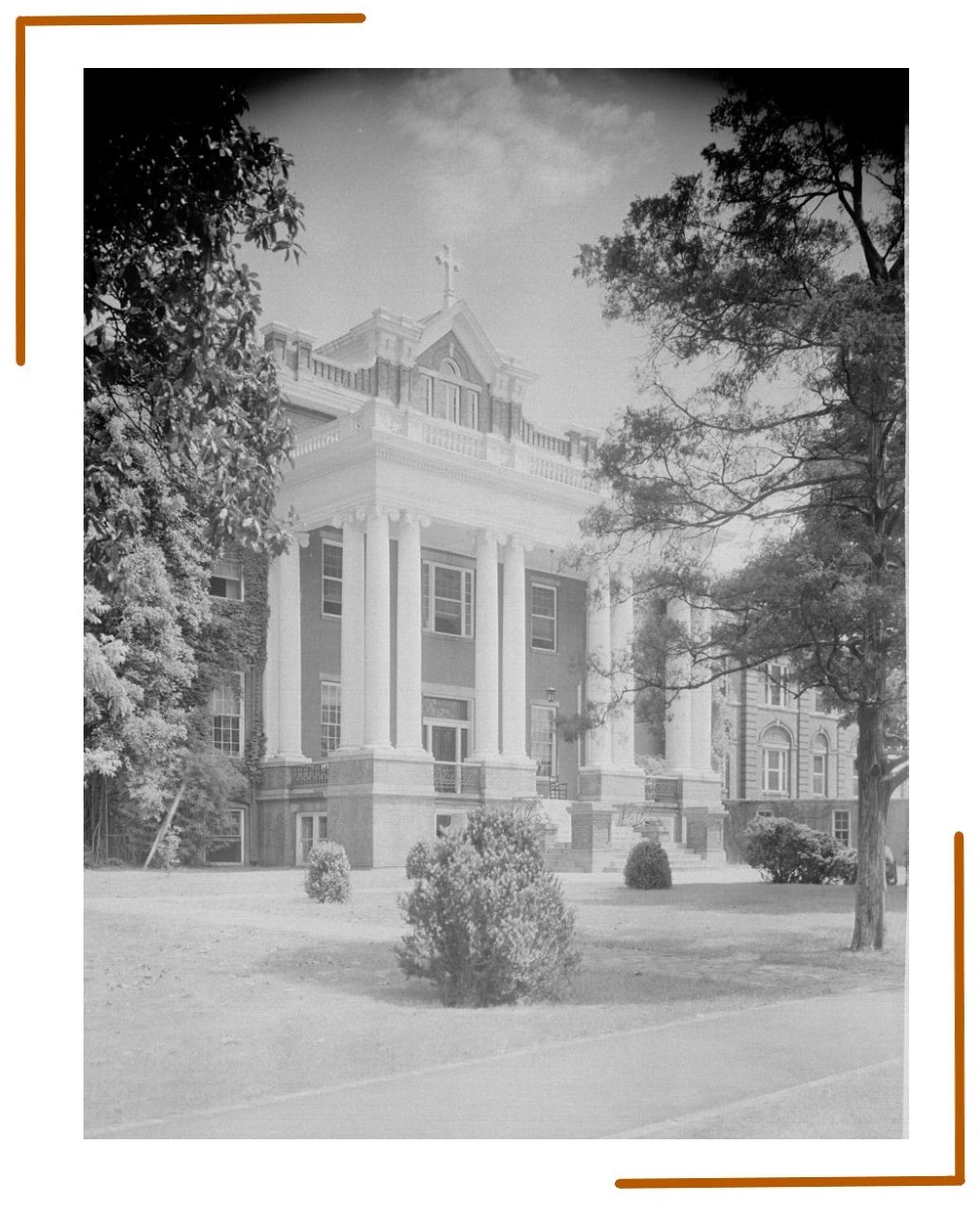

Margaret Elizabeth Cotten (1835-1895) was a young woman who attended St. Mary's School in Raleigh prior to the Civil War. The daughter of John Whitaker Cotten and Laura Placidia Cotten (née Clark), she was born into two prominent and influential high society families, which afforded her a variety of connections in North Carolina society. Her status provided her with both the money and the education that many women of the time did not receive, but these privileges came as the result of her family's enslavement of various people.

This diary provides a look at Margaret Eliza Cotten's life from October 1853 to July 1854, from age seventeen to eighteen, ending a year before her marriage to Joseph Adolphus Engelhard. Most of her entries record her daily activities, ranging from traveling up to St. Mary's School, to visiting Wilmington for Christmas, to interactions with various close friends and potential suitors.

Family Structures

Margaret Eliza Cotten was the eldest child of John Whitaker Cotten and Laura Placidia Cotten (née Clark), preceding three children born after her. When Cotten was ten years old, her father died in Florida, leaving behind his wife, three daughters, and his soon-to-be born son. He left his family under the guardianship of his brother and brothers-in-law, but not his wife. Seven years after his death, John Whitaker Cotten is not mentioned in Margaret's diary, but that does not mean his absence has not affected her. Outside of her mother and grandmother, Cotten seems distant from many members of her family. Without the guidance of a typical father figure, many decisions appear to be entirely her own.

Life of a Young Woman in Raleigh

Suitors, Courtship, and Marriage

For a young eligible woman of means, marriage was seen as a necessary step. By her eighteenth birthday, it was likely that getting married and finding a husband was a chief concern among Margaret's friend groups and family. Marriages among the elite in 1850s Raleigh could be for love, but could also be for money, stability, and patriarchal expectations. Margaret was not naive of these outcomes and stated herself that she hoped to never fall in love or marry, perhaps for personal reasons or in recognition of her own rights and privileges. Several close female family members, such as Maria Toole Haywood and Eliza Eagles Haywood, never married, and lived their lives single with the money to do so.

Marriage for Margaret would have meant losing a level of her own financial independence and having to submit to a man's authority. Losing her father at a young age undoubtedly shaped her family dynamic, and though she was placed under the guardianship of her uncles, she also gained independence other young women did not have. Her interactions with potential suitors, who accompanied her on walks and to parties, demonstrate that many were interested in her hand in marriage. In the spring of 1854, Margaret received a letter from someone she would not name, stating he was in love with her, with feelings she did not reciprocate.

Records show that in late 1855, a little over a year after the end of her diary, Margaret married Joseph Adolphus Engelhard, with whom she was close friends with during the time of her diary. As no other diary from Margaret exists, we do not know how she felt about her wedding and eventual marriage. They would go on to have four children together and lived in North Carolina until Engelhard's death in 1879. She never remarried.

"Popping the Question" created by lithographer Sarony & Major circa 1846. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

"The Marriage" created by lithographer Sarony & Major circa 1846. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On the Eve of War, Emancipation, and Reconstruction

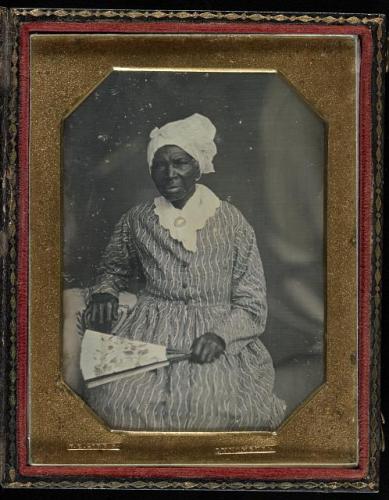

"Mary Bryce (or Brice) of Point of Honor, Lynchburg, Virginia" circa 1853. Taken by photographer Peter E. Gibbs. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Taken from around the time Margaret Eliza Cotten's diary, this daguerreotype shows one woman who was enslaved during the 1850s.

Slavery and Emancipation in Raleigh

Through the wills of the Cotten family and Margaret's diary, it is evident that they enslaved around twenty people. Unfortunately, these individuals are often omitted from the narrative. The Cotten family's wealth could only be amassed through the exploitation of the enslaved, but in Cotten's diary, enslaved people's contributions and stories are pushed to the background. Unfortunately, in Margaret's mind, they are an afterthought in the record of her day-to-day activities, even though these enslaved individuals were what made her life possible.

In 1870 census records, several individuals mentioned in the diary can be found, then living free in Raleigh. Fountaine and Malvina by 1870 were living in the area and working for a wage. While their whole story cannot be told from just these census records, it demonstrates the newfound freedoms that enslaved people had following the Civil War and Emancipation. Both of them had taken on the last name "Cotten" or some variation of it, as was common for emancipated individuals to take on their former enslaver's name. Other individuals, such as Virgil, Davy, and Henrietta could not be located post-emancipation and may have moved or taken on other names.

"Davy brought Mollie's and my own daguerreotype, also a note from Mr Saunders"

- Diary Entry from Margaret Eliza Cotten, 12 November 1853

"It was too rainy for Fountain to go to the office - and oh! how I hope I will receive one"

- Diary Entry from Margaret Eliza Cotten, 11 July 1854

"Henrietta has just commenced fixing my hair for the night and I will devote the few moments before retiring to my journal."

- Diary Entry from Margaret Eliza Cotten, 11 July 1854

"I give to my wife my carriage and carriage horses and Virgil for a Driver."

- Will of John Whitaker Cotten, 1845

"Did not get home 'til nearly three—Malvina had me a nice supper of oysters all hot and nice, when I did come."

- Diary Entry from Margaret Eliza Cotten, 11 January 1854

Civil War and Reconstruction

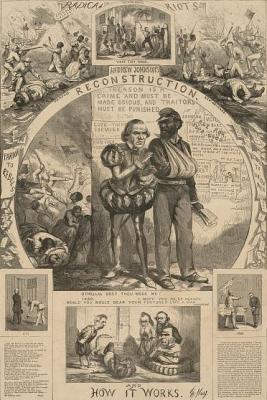

By July 1854—the end of Margaret's diary—the Civil War was fewer than seven years away. Many of the young men in her life would join various North Carolina regiments in the Confederacy. Her future husband, Joseph Engelhard, rose to the rank of major during the war. Some men, like Joseph Wright and James "Jimmie" Wright both died fighting for the Confederacy. It seems though, that most of the young men in Margaret's life did survive. After the war, Reconstruction began in North Carolina. For his strong Democratic beliefs, Engelhard was elected secretary of state and was re-elected in 1866. He also became editor of the Wilmington Journal, which by then had statewide circulation. Through both his role as editor and his position as secretary, he encouraged the reworking of the State Constitution to prevent African American men from entering local government and from receiving benefits from the federal government. Engelhard's close friend, William Saunders, was involved in the Ku Klux Klan and simultaneously worked with Engelhard on the Wilmington Journal. This shows just how North Carolina's elite families worked to maintain antebellum social hierarchy and the exploitation of the formerly enslaved in the South, long after the Civil War.

"Andrew Johnson's reconstruction and how it works" by Thomas Nast, from 1866. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This engraving shows President Johnson as Iago and an African-American veteran as the eponymous Othello. The snakes named "CSA" and "Copperhead" attacking another man show how Reconstruction would begin to fail in the South.

Conclusion

How Women are Remembered and How We Research the Past

Margaret Elizabeth Engelhard (née Cotten) died in January 1895, having outlived her husband by about sixteen years. Her obituary in the Raleigh News and Observer from February 1st of that year opens with the words: One of Raleigh's Best Known and Honored Women Passes Away. Little is said however, about her accomplishments or personality outside of her parentage, husband, and children. Noted, is her general unwillingness to leave Raleigh and to leave her husband's grave. It is possible that some of her fears about marriage were realized. With no other diary currently known, Margaret Eliza Cotten's diary from 1853-1854 is our main source that provides insight into her thoughts and perspectives. Often times, the sources from women are limited, and her diary in the North Carolina State Archives is a useful tool to look at Raleigh from the 1850s, but one of just a single perspective.

"Miss Rosabelle Engelhard" taken in Raleigh, circa 1890-1895. Courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives.

Though Margaret mentions having several daguerreotypes taken, none of these photos are known to survive. This photo is of Rosabelle Engelhard, her third child with Joseph Engelhard. She was partially named for Engelhard's sister, Rosa, and for Margaret's sister Arabella.